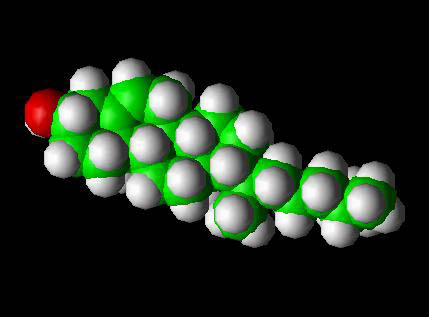

Research in the 1950s introduced the idea that heart attacks are the result of excessive consumption of animal food products, which raises the level of cholesterol in the blood. As research continued, it eventually became clear that high blood cholesterol levels could be the cause of the heart attack epidemic, largely through the findings of the American physiologist Ancel Keys. Keys completed his scientific work with a landmark epidemiological study concerning the triangular relationship between blood cholesterol, saturated fat intake and heart attacks in seven countries.

In 1954, Dudley White, then president of the World Congress on Cardiology, asked Keys to organize an epidemiology conference in Washington. It was at that conference that the idea was put forward for international collaboration that would clarify once and for all the role of dietary fat and blood cholesterol in heart disease. Seven countries participated in the study: the United States, Japan, Finland, the Netherlands, Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece, the majority of which Keys was familiar with from his previous research.

Each country undertook to provide Keys and his collaborators with suitable study participants – healthy men aged between 40-59 years – who included 2,571 railroad workers from the USA, 1,010 farmers and fishermen from two Japanese villages and 1,215 farmers from the Greek islands of Crete and Corfu. In total, 12,763 men from 16 rural laboring populations were enrolled, the aim of the study being to compare their mortality rates over time and assess the role of diet. Periodically, assistants were sent to the homes of study participants to collect food samples, which were then analyzed in the laboratory.

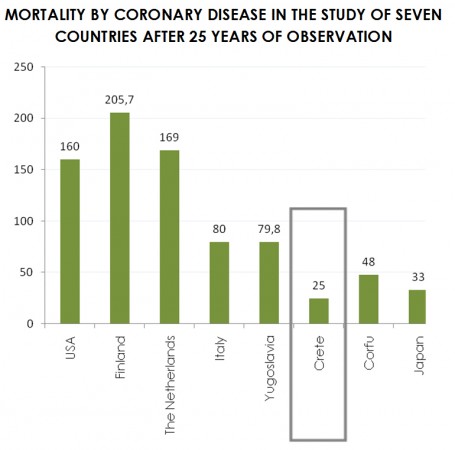

After 15 years of monitoring, the Seven Countries Study showed that, in general, the more cholesterol there was in the blood of a population the higher its mortality rate from heart attacks. The Eastern Finns were in the worst position on the list, with the highest blood cholesterol, 264 mg/dl, and 1,202 deaths per 10,000 people. The Americans were in second worst place, with 240 mg/dl and 773 such deaths. Less prone still to myocardial infarction were the Japanese, with the lowest blood cholesterol level, 165 mg/dl, and only 135 deaths.

However, there were some exceptions to the pattern which emerged, the most striking being that of the Cretans. The Cretans had a level of 202 mg/dl blood cholesterol, which was close to the average of 211 mg/dl for all the populations included in the Seven Countries Study, yet they had the fewest heart attacks: only 38 per 10,000 people or three times lower than the Japanese. As a whole, the Greeks took second best place after the Japanese, as amongst the male population of Corfu there were 202 fatal heart attacks per 10,000 people.

As the years passed, the number of deaths from heart attacks increased in all populations of the Seven Countries Study but the order remained about the same. After 25 years of monitoring, the Cretans had 25 deaths per 1,000 men, the Japanese 33, the Americans 160 and the Eastern Finns 268.

Keys concluded that the Seven Countries Study confirmed the destructive role of saturated fat. The Japanese had the lowest intake of saturated fat, just 2.9 percent of their total calories, and the Cretans 7.7 percent. In contrast, the Finns obtained 23.7 percent of their calories from saturated fat and the Americans 16.2 percent. However, if one took a closer look at the data there were again some exceptions. The Japanese, the Greeks in Corfu and the Serbians in Velika Krsna consumed less saturated fat than the Cretans, yet without having fewer heart attacks.

Keys concluded that the Seven Countries Study confirmed the destructive role of saturated fat. The Japanese had the lowest intake of saturated fat, just 2.9 percent of their total calories, and the Cretans 7.7 percent. In contrast, the Finns obtained 23.7 percent of their calories from saturated fat and the Americans 16.2 percent. However, if one took a closer look at the data there were again some exceptions. The Japanese, the Greeks in Corfu and the Serbians in Velika Krsna consumed less saturated fat than the Cretans, yet without having fewer heart attacks.

The Seven Countries Study did not show that total fat consumption played a role in the incidence of heart attacks, as the Cretans had a high total fat intake amounting to about 40 percent of their calories. Neither was a close correlation found between smoking and heart attacks – the Japanese smoked more than the Finns – nor was obesity found to play an important role. In short, the Seven Countries Study confirmed what Keys already believed played a role in myocardial infarction; and it was later said that he had used statistics to prove his theory.

Although Keys was often mentioned as a candidate for a Nobel Prize it is an award that has never been given to an epidemiologist, perhaps because, by their very nature, epidemiologic studies involve statistical correlations that may have to be revised when more information becomes available in the future. And, indeed, the paradox of the Cretans was to undermine Keys’ theory in later years.